The Science of Dragons

Have you ever wondered how dragons can fly, despite their bulk? Or how they breathe fire? Or why they hoard gold? Author Peter Dickenson figured out an answer, and wrote about it in a book called The Flight of Dragons, which was later adapted into an animated movie by Rankin-Bass, made in 1982 and telecast in 1986.

At his website he wrote:

This one had a bulky body and rather stubby wings, which obviously would never get it airborne, let alone with the two people it was carrying on its back, and all its own weight of muscle and bone. Obviously any lift had to come from the body itself. Its very shape suggested some kind of gas-bag. I thought about it for the rest of the journey, and on and off for a couple of days after, and at the end of that time had managed to slot everything I knew about dragons – why they laired in caves, around which nothing would grow and where hoards of gold could be found, why they had a preferred diet of princesses, how and why they breathed fire, why they had only one vulnerable spot and their blood melted the blade of the sword that killed them, and so on – into a coherent theory that explained why these things were necessary accompaniments to the evolution of lighter-than-air flight.

His theory was interweaved with the story of The Flight of Dragons. See for yourself:

The Honesty of Lumatic Animation

Usually when a studio licenses the media rights to a book, the studio will make certain creative decisions that differ from the author’s presentation. Characters may change. Characters may disappear. Not every scene in the book is filmed. New scenes are added. Whatever the reason, the explanations for these choices are usually not made known to the public.

Constantin Film and Lumatic Animation & VFX Gmbh adapted Cornelia Funke’s Dragon Rider for cinemas and ultimately, for streaming. For certain territories, they retitled the film Firedrake the Silver Dragon. Lumatic posted a webpage devoted to how the film was made, with great detail.

What is remarkable is this: Lumatic reveals why their creative choices differ from the book.

For example, Lumatic’s Firedrake is not Cornelia Funke’s Firedrake. Why?

Here’s the explanation:

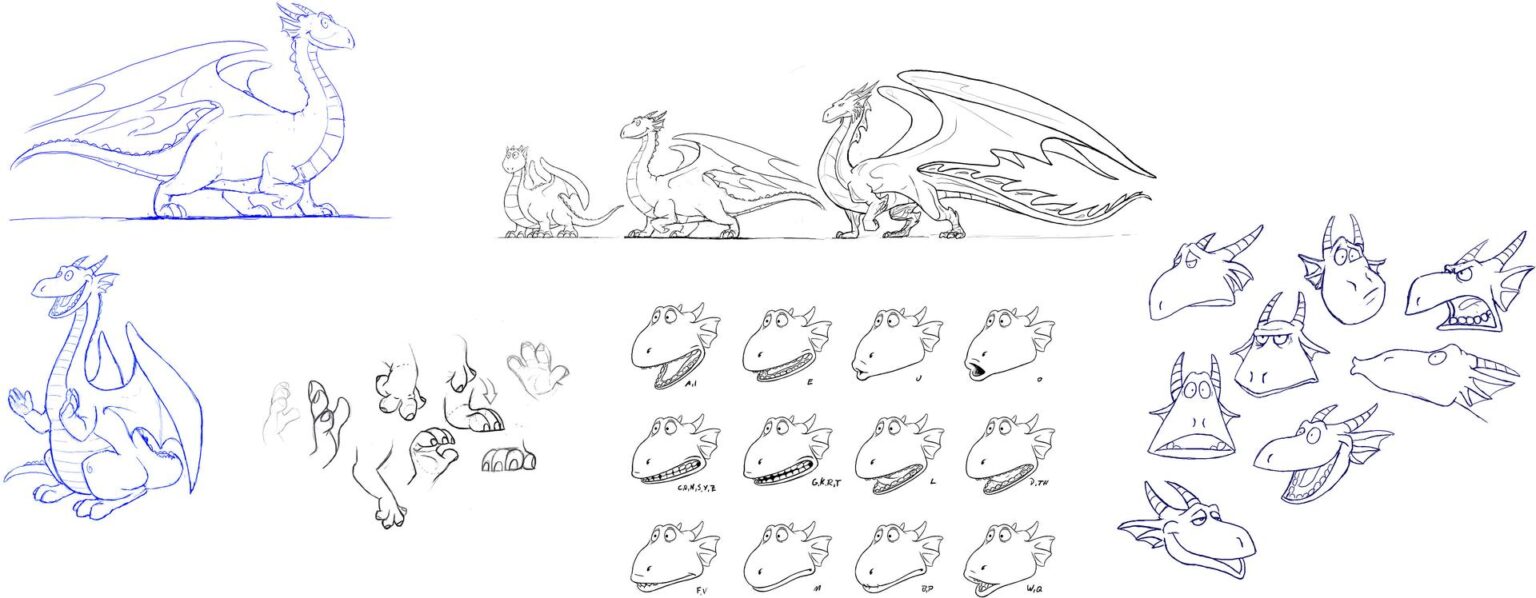

“… in the book he is featured as a mature dragon. The decision to make him a younger character in the film was made in order to achieve a group dynamic between him, Ben and Sorrel, that would more resemble classic films like Stand by Me, Goonies and many more, where a group of kids go out to a secret adventure, without the knowledge of the grown-ups around them. His base design as a winged quadruped was partially based on Cornelia Funke’s original illustrations, but his final design ended up drifting into a more naive and likable direction, after it became clear that he is going to appear as a younger character in the film. Classic dragon features like sharp teeth, spiky horns, and other monster-like features were strongly reduced in order to reflect his friendly, nonthreatening nature. His lower body was designed according to the anatomy of a lion cub, to convey majesty and a future leader.”

Frankly, I like Lumatic’s version of Firedrake. He’s a lovable, innocent, loyal and determined character. The design, animation, and Thomas Brodie-Sangster’s winsome vocal performance reflect that personality. It’s likely we won’t see this version again, and that’s a shame.

Lumatic’s website mentions other deviations from the novel, and rationale for why the changes were made. This, again, is remarkable.

Visit Lumatic’s Making of Dragon Rider / Firedrake the Silver Dragon to learn more.

How to Announce Your Dragon Premiere

October 3, 2020. Director Tomer Eshed posts a Facebook video announcing the premiere of the English-language version of Dragon Rider at the Festival of Animation, Urania, Berlin in Germany. Watch for the surprise at the end.

If this isn’t visible in Firefox try viewing it in Chrome or another browser.

or click on this link.

What happened to the samosa?

Seeking directions to the Rim of Heaven, Firedrake and his companions arrive at the Temple of the Dragon Rider in India. Subisha Gulab, the local guru, tells them the prophecy of Varin, the first Dragon Rider. Her husband Deepak arrives with a plate of samosa to refresh the visitors. He sets the plate on a table.

Subisha shoos away her annoying husband.

Firedrake and friends watch.

Subisha returns to the table.

What happened to the samosa?

Side by Side with Firedrake

From Constantin Music, “Side by Side,” composed by Stefan Maria Schneider, sung by Reema, featuring a montage of clips from Drachenreiter / Dragon Rider / Firedrake The Silver Dragon:

Details in German, here.

Jawad Buddy presents the full extract from the film, here:

https://youtu.be/EepMV585vEg#t=0m4s

Lumatic calls this “The Montage Sequence,” and these are their notes:

The Montage sequence is a series of short shots that show different locations through which our heroes have to fight their way. A lovely song underlines in an ironic way the many absurd situations they get into. The places are wildly mixed up to illustrate the disorientation of our would-be adventurers. Here, some places are dealt with in quick succession, which are given significantly more leeway in the script or novel.

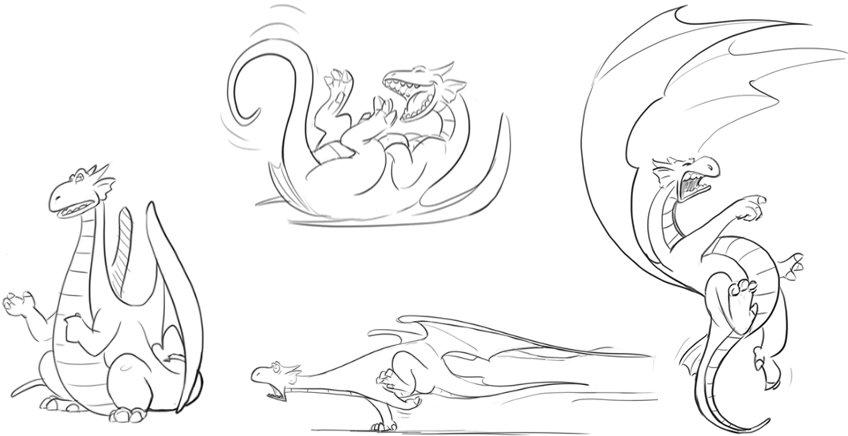

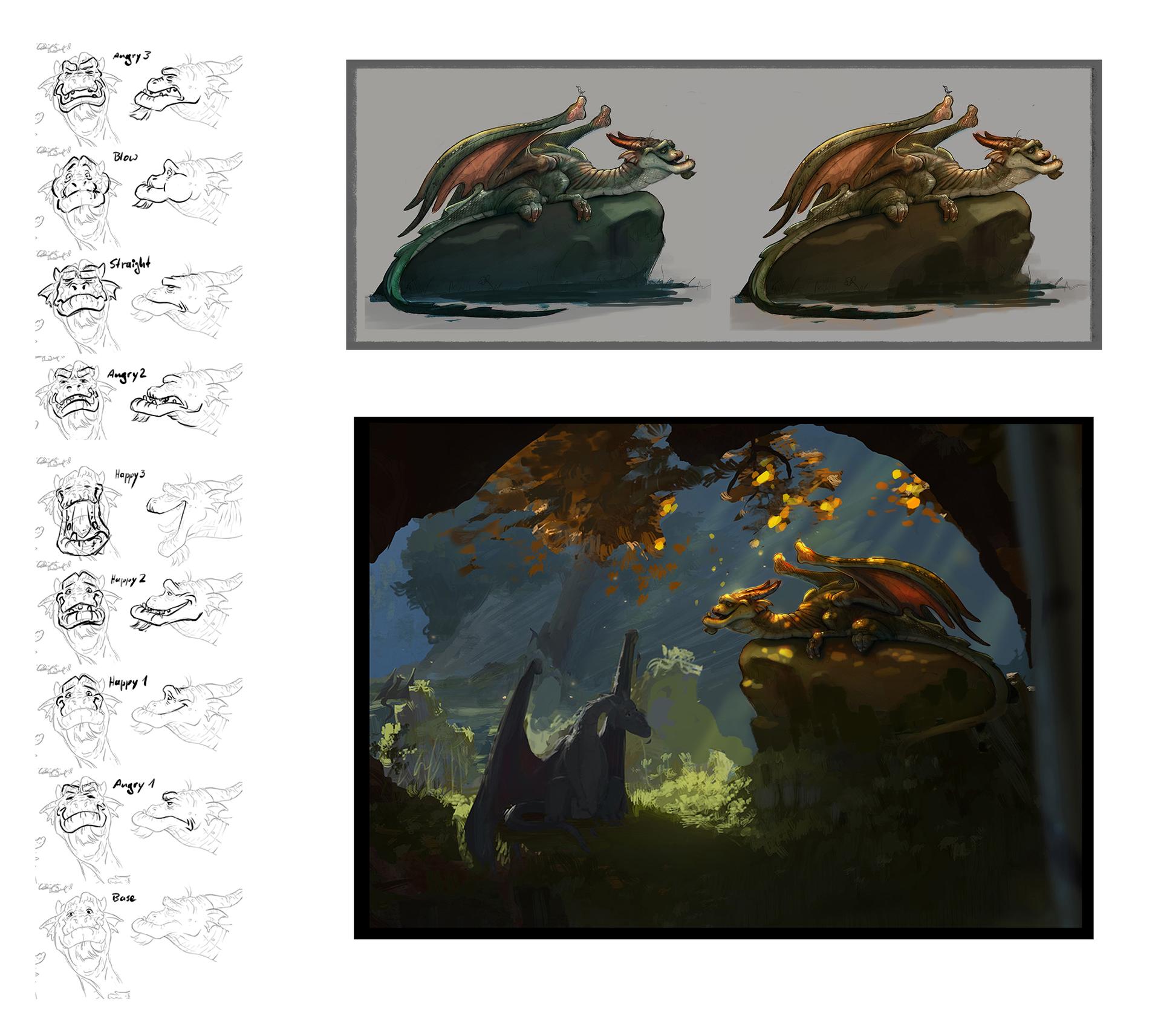

Drawing Firedrake

From Lumatic’s “Making of Dragon Rider” webpage, some nice, expressive drawings of Firedrake the Silver Dragon. Click the image to unsqueeze and enlarge.

What’s His Name?

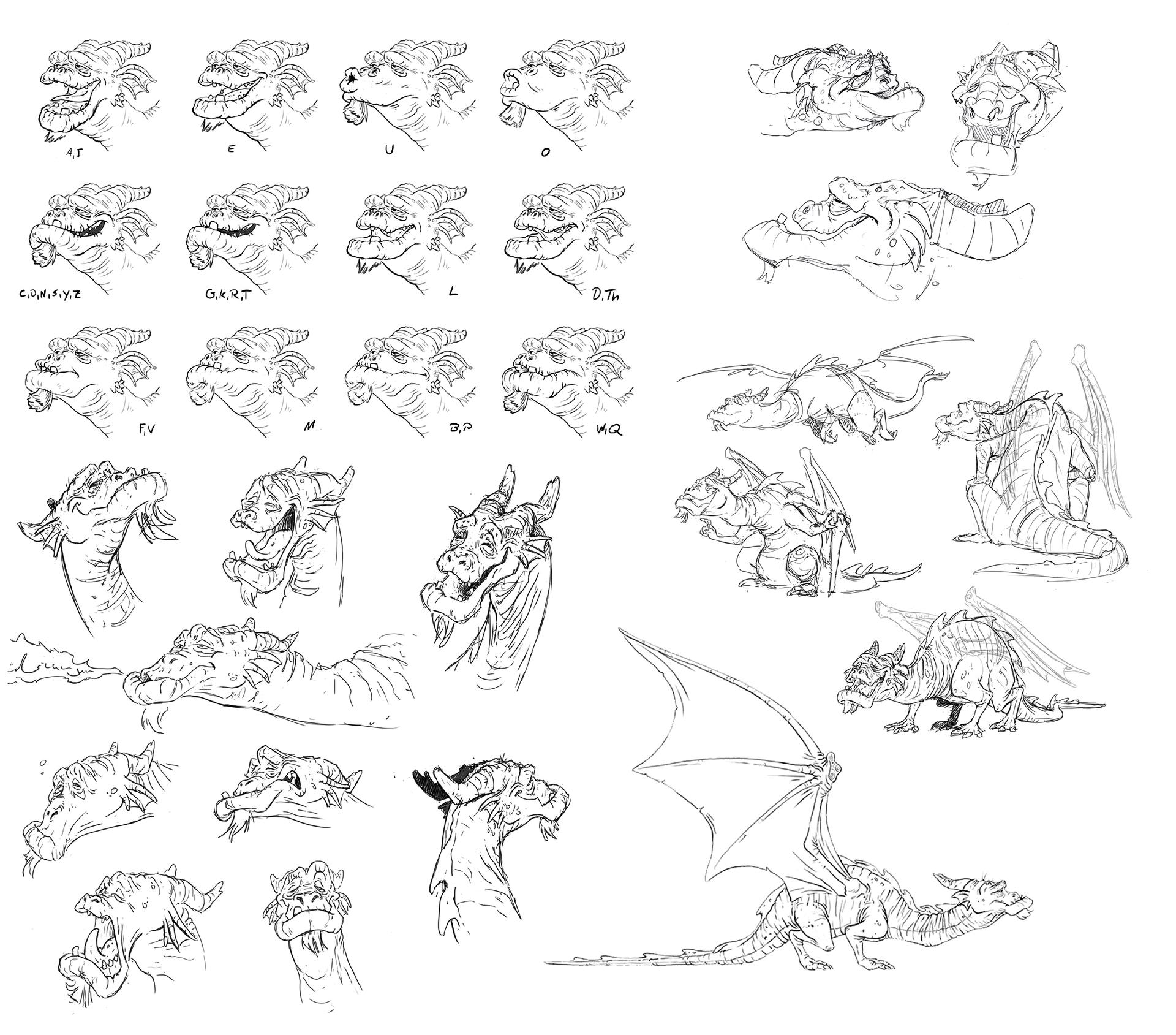

Slatebeard. He’s the wise ol’ dragon in Dragon Rider aka Firedrake The Silver Dragon. Alas, the only one who will listen to him is Firedrake, and that is, the Rim of Heaven is where their kind can go for refuge. Firedrake, our hero, decides to find it.

Below are some character designs posted by Lumatic. Nice, aren’t they? Click on the image to enlarge it.

Once I learn the artist’s name, I’m happy to provide credit.

Slatebeard is voiced by Peter Marinker.

For more on the making of Dragon Rider, visit Lumatic’s website.